Sales at Yiheng Battery were stagnating in the fall of 2022. The company, based in the eastern Chinese city of Yiwu, had done good business for 30 years selling button cell batteries — used in watches and other small devices — to customers at its factory and on Chinese shopping platform 1688. But the Covid-19 pandemic had taken a toll. “The [Chinese] economy was not doing well, and people were not spending,” Huang Qianqian, whose parents own the factory, told Rest of World. That October, Huang, 28, quit her job at a tech company to help out the family business.

Huang’s friends eventually told her about a new e-commerce platform, Temu, which had just launched in the U.S. Temu is owned by PDD Holdings, which also owns Pinduoduo, a Chinese online shopping app that is popular in China for its low prices and gamified features. Temu used similar tactics, but targeted American customers.

Huang convinced her parents to give Temu a try. It could be an opportunity, she reasoned, to take the business international. “A lot of second-generation factory owners like me will seek to break new ground when they start to take over the family business,” she said. “Temu’s launch felt like just the right time.” Yiheng Battery joined the platform in December.

Temu has caused a stir in Yiwu, which is famous for its sprawling wholesale markets. “Every time a platform rises to prominence, a large number of suppliers get rich here in Yiwu,” Huang said. “It used to be Amazon, [domestic e-commerce app] Taobao, and then Pinduoduo. Lately, a lot of people want to hop on the Temu train.”

China has been “the world’s factory” for decades, with made-in-China goods reaching global consumers through foreign brands, shops, or sites like Amazon. And the country has had a vibrant domestic e-commerce sector, with companies like AlibabaAlibabaAlibaba, founded in 1999 by Chinese entrepreneur Jack Ma, is one of the most prominent global e-commerce companies that operates platforms like AliExpress, Taobao, and Tmall.READ MORE and JD.com growing into juggernauts.

But recently, Chinese-owned shopping platforms have begun looking beyond China’s borders. Temu joins ultrafast-fashion platform SheinSheinFounded in China in 2008 and headquartered in Singapore, Shein is a fast fashion brand that grew rapidly through exposure on social media.READ MORE and TikTok’s shopping feature TikTok Shop to herald a new, global era for Chinese e-commerce. Yao Kaifei, founder of e-commerce startup BrandAI, told Rest of World the country’s e-commerce sector is desperate to chuhai, or venture overseas. Sellers and platforms want to shed the reputation of selling cheap “made in China” gadgets, and make a name for themselves exporting whole brands and business models.

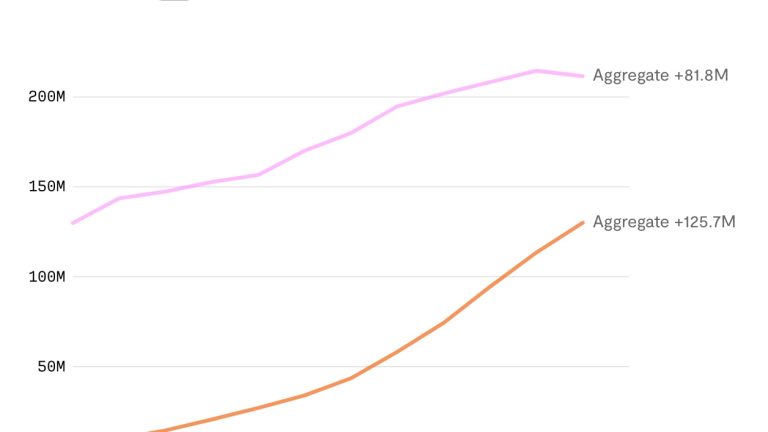

By September 2023, roughly a year after its launch, Temu had more than 61 million monthly active users in the U.S., according to research company Data.ai. It now sells in 48 countries around the world. Shein is one of the world’s biggest fast-fashion companies and has branched out to selling other products, such as homewares and electronics. It has been the top-ranked shopping app on the Google Play store in 115 countries, according to Data.ai. TikTok Shop, meanwhile, has seen quick growth in Southeast Asia, and launched in the U.S. this September.

The platforms have reshaped global e-commerce, both for customers and sellers. In Yiwu, Huang’s efforts to move her family business onto Temu have resulted in around 100 orders a day, although she said they make very little profit from the platform, owing to cutthroat pricing. In any case, she’s already eyeing her next venture: selling pet products on TikTok Shop. “I heard that a two- to three-person team running a TikTok Shop can easily make millions of yuan a year,” she said.

“In the ’90s, [Chinese] manufacturers saw themselves as mere suppliers at the lower echelons of the value chain,” Yao said. But the sales channels provided by the new apps give them access to consumers almost anywhere, spawning global aspirations. “What was once unthinkable for Chinese sellers is now within reach.”

On November 11, 2009, Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba launched a shopping festival that has since become the most important date for the country’s e-commerce sector: Singles Day, or Double 11. In its inaugural year, it brought $7.8 million in sales.

That figure climbed year on year. By 2019, Singles Day was a star-studded event: Kim Kardashian shilled for Singles Day in a special livestream; Taylor Swift performed an evening concert in Shanghai before the big discounts kicked in at midnight. That year, Alibaba made its first billion dollars in sales in just one minute and eight seconds. Twenty-four hours later, the counter stood at $38.4 billion, another record.

Then, trouble began. In 2020, the Chinese government started clamping down on the country’s tech sector. Alibaba founder Jack Ma had made comments about China’s financial regulations, drawing particular ire from officials. A series of strict citywide lockdowns during the Covid-19 pandemic were followed by a wobbly economic recovery. In 2022, Alibaba kept its Double 11 sales numbers secret for the first time.

Lin Zhang, an associate professor at the University of New Hampshire who studies e-commerce, told Rest of World the saturation of the domestic market spurred an interest in reaching international markets. “They have the money. They have the experience. They know there is a gap out there in the international market,” Zhang said. “And it’s so tough domestically. So why don’t we go [overseas]?”

Shein was an early mover in the chuhai ambition. Founded in 2008 in Nanjing, it exclusively targeted international customers from the start. Sales climbed through the 2010s, but it took the pandemic to make Shein go truly viral. The company’s social media strategy popularized #sheinhaul videos, in which creators sometimes tried on more than 100 items in one go. The app’s global sales surged from a reported $4 billion in 2019 to $23 billion in 2022.

According to Juozas Kaziukėnas, founder of e-commerce analyst firm Marketplace Pulse, Shein’s strength is its ability to offer thousands of new items every day. It runs a flexible supply chain that sources from a vast network of Chinese apparel factories and quickly adjusts to customer sentiment. For customers, a key draw is Shein’s low prices. According to one analysis, Shein’s prices for women’s fashion products are on average 39% to 60% cheaper than those of H&M.

Juliana Silva, a hospital psychologist from São Paulo, Brazil, told Rest of World she became a loyal Shein customer after seeing its Instagram ads for plus-size clothing. “It really annoys me when I go to [Brazilian department stores] Renner or Riachuelo, and I see a top that I know is the same or very similar to what Shein offers, but there it’s being sold at an outrageous price,” she said.

In 2023, Shein launched an Amazon-like marketplace for Chinese and international sellers to stock products, including electronics, DIY tools, and appliances.

When Temu launched in September 2022, it also drew people in with low prices. In February, it broadcast an ad during the Super Bowl encouraging viewers to “shop like a billionaire” and fill their virtual carts without having to worry about the cost. That weekend, Temu racked 426,000 app downloads in the U.S., according to digital analytics company Sensor Tower.

“Globally you have an economic slowdown, so a lot of consumers are also spending less per platform,” Sharon Gai, the former head of global key accounts at Alibaba and author of Ecommerce Reimagined, told Rest of World. “When there’s a low-cost e-commerce platform that’s emerged out of nowhere, they are obviously going to like it.”

“I got addicted from the games.”

Like its Chinese sister app Pinduoduo, Temu also brought gamification to the shopping experience. Visitors to the platform can play a virtual farming game or feed virtual fish to win free items, with extra incentives if users keep coming back or invite their friends. “I got addicted from the games,” one American Temu shopper, 24-year-old care worker Maddie Young, told Rest of World. She earned freebies like a unicorn backpack and a coffee machine by playing Temu’s games and bought clothes for her three children. “Temu and Amazon are very similar, they sell some of the exact same things,” she said. “But Temu is cheaper and [has] free shipping.”

Gai said the platforms had fortuitous timing, as they emerged just as online sales in China slowed: “Factories and sellers in China will bend to these low prices because this has been a tough year for them domestically.” She said manufacturers might accept lower margins initially, in the hope the platforms would bring increasing orders.

Several Chinese sellers told Rest of World the platforms also made it easy for them to join. “Amazon and Taobao are like malls,” said Huang, from Yiheng Battery. “But Temu and Shein are like supermarkets. You supply unbranded products to the platform and let them take it from there.”

This hands-off model is particularly attractive to businesses that have little experience marketing abroad. Lin Qianran, who runs a lighting company in the southern Chinese city of Zhongshan, said many traders in the area had joined Temu. Lin said her margins on Temu are about half those on Amazon, but Temu requires less effort. She also opened a store on Shein this year. “Their entry barrier is not as high as Amazon’s,” she said.

One day in 2021, Thesalonica Gita Pramesti Putri, a 28-year-old food stall co-owner in the Indonesian city of Yogyakarta — who goes by Thesa — was scrolling through TikTok when she noticed something new. Between the typical videos of viral dances and comedy skits, there were livestreams of people trying to sell fashion and beauty products directly to viewers.

TikTok Shop had launched in Indonesia in April 2021, amassing sales worth $2.5 billion within its first year and subsequently launching in Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Thailand.

Thesa was intrigued: As a university student, she’d made money by drop-shipping fashion accessories, and she sensed an opportunity. Thesa and her fiancé started selling clothes made with traditional Indonesian fabrics and soon attracted buyers, especially after they paid to have their livestreams feature in users’ For You feeds. They have hired eight employees to sew clothes, host livestreams, and pack orders. This September, they made around 90 million rupiah ($5,730).

This kind of social commerce was pioneered in China by Alibaba, which introduced shopping livestreams on its Taobao app in 2016. Livestream hosts hawk anything from makeup to laundry detergent, with some gaining huge followings and selling billions of dollars of products. One of China’s most famous e-commerce influencers, Austin Li, also known as the “Lipstick King,” once sold 15,000 lipsticks in five minutes.

Livestream shopping has become a mainstay of Chinese e-commerce. On Douyin, TikTok’s Chinese sister app, consumers bought $208 billion worth of goods in 2022.

TikTok Shop is trying to replicate this success outside of China, with an initial focus on Southeast Asia. In August, research firm Momentum Works reported that the app’s sales in the region were on track to grow from $4.4 billion in 2022 to a target value of $15 billion in 2023.

But the livestream shopping model hasn’t worked everywhere. TikTok Shop launched in the U.K. in 2021 to a lukewarm reception that caused it to pause plans to roll out in Europe and the U.S. the following year. TikTok eventually expanded the shopping feature to the U.S. this September, hoping to turn its more than 150 million American users into regular shoppers. A TikTok influencer who posts under the name Coco Mocoe was among the first in the U.S. to use the feature, hawking a fluffy handheld microphone to her 1 million followers. The product sold out in a day. “China and the way that they use media is always a few years ahead of us,” she told Rest of World.

The same month as the U.S. launch, however, TikTok Shop was dealt a significant blow: In a bid to protect local businesses, the Indonesian government announced it was going to ban social media apps from selling products. On October 3, Thesa received an email from TikTok announcing it was closing TikTok Shop in Indonesia. She would no longer be able to sell her clothes on the platform. “I was aghast,” she said.

She has since started livestreaming on Shopee, a Singapore-headquartered e-commerce platform, but said her income has dropped by more than half. In response to questions about the ban, TikTok Indonesia referred Rest of World to a statement that said the company “will continue to cooperate with the relevant authorities on the path forward.”

“China and the way that they use media is always a few years ahead of us.”

Bhima Yudhistira Adhinegara, executive director of the Jakarta-based research institute Center of Economic and Law Studies, told Rest of World the government’s ban won’t have the effect it is hoping for. “E-commerce is not heavily regulated, so the impact of TikTok Shop closing is only partial,” he said. He pointed out that, like Thesa, most sellers just migrated to other platforms.

Indonesia could be setting an example. In October, Malaysia’s government hinted it was considering a similar policy, as its communications and digital minister said he had received complaints from local stores about TikTok Shop and raised concerns about “predatory pricing.”

Elsewhere, competitors and regulators are also zoning in on the new generation of Chinese shopping platforms and their ultralow prices.

Rafaella Torneri, who co-owns an online women’s clothing store called Guardaroba, based in São Paulo, told Rest of World her locally manufactured products were once priced competitively with other Brazilian brands, but Shein changed the game. “It used to be much easier for us,” she said.

In August, the Brazilian government changed its regulations to increase taxes on imported packages valued below $50, which it said was aimed at foreign e-commerce platforms. In a statement to Rest of World, a PR representative for Shein in Brazil said the company welcomed the new tax program and that it had been subsidizing the increase in tariffs for its users.

U.S. lawmakers have also been considering a change to import tariffs, accusing Shein and Temu of taking advantage of a rule that allows packages shipped individually to avoid tariffs, giving them an edge over businesses that ship by the container. A June report by a House of Representatives committee found that H&M and Gap paid $205 million and $700 million in import duties in 2022, respectively. Meanwhile, Shein and Temu paid nothing on the vast majority of their direct-to-customer shipments.

In July, Shein’s executive chairman, Donald Tang, said U.S. tariff policy on imports valued under $800 needed “a complete makeover” to create a level playing field for retailers. In an emailed response to Rest of World, Shein said it is committed to respecting human rights, providing a safe and fair work environment for workers, and protecting intellectual property. TikTok referred Rest of World to its previous statements on TikTok Shop in the U.S. and Indonesia. Temu did not respond to a request for comment.

The platforms’ low-price strategy also puts pressure on sellers. Zhang Zhouping, a cross-border e-commerce researcher at Hangzhou-based consultancy 100ec.cn, told Rest of World that platforms like Temu pose a dilemma for sellers: Lower your margins and enjoy higher sales, or be left out.

“The lowest price always wins.”

“The lowest price always wins,” Queenie Zhang, who runs a Shenzhen-based business selling home products across various platforms, told Rest of World. She joined Temu but soured on the experience and quit. “For a product that costs us $12.30 to make, [Temu] are offering to pay $11.30,” she wrote on social media in July. “We couldn’t accept that and could only give up selling this product.”

It’s unclear how long Temu can keep its prices so low. In its bid to attract customers, the company also subsidizes shipping while spending aggressively on marketing. Chinese tech publication 36Kr estimated that Temu is losing $40 on every $100 earned in sales, citing sources familiar with the matter. During an earnings call in August, Liu Jun, vice president of finance for Temu’s parent company PDD Holdings, said Temu was still in its “learning phase” and was not yet focused on monetization. Gai, the former Alibaba executive, said Temu was using small, low-priced items to rapidly grow its user base, and that she expects the company will continue to scale back its free shipping policy.

For now, this strategy continues to fuel astounding growth. As the Northern Hemisphere gears up for its winter holiday season, the platforms are battling for both customers’ and sellers’ attention by redoubling their focus on bargain prices. TikTok is offering to subsidize discounts of up to 50% to encourage sellers to participate in its Black Friday program, and Temu is advertising a holiday sales event that offers up to 90% discounts.

Shein, meanwhile, launched an “11.11 shopping festival” — its own take on China’s Singles Day. “Self-control can wait, we’re having a self-care moment,” the company wrote on Instagram.